Afrofeminism in France and Abroad: A Q&A With Fania Noel

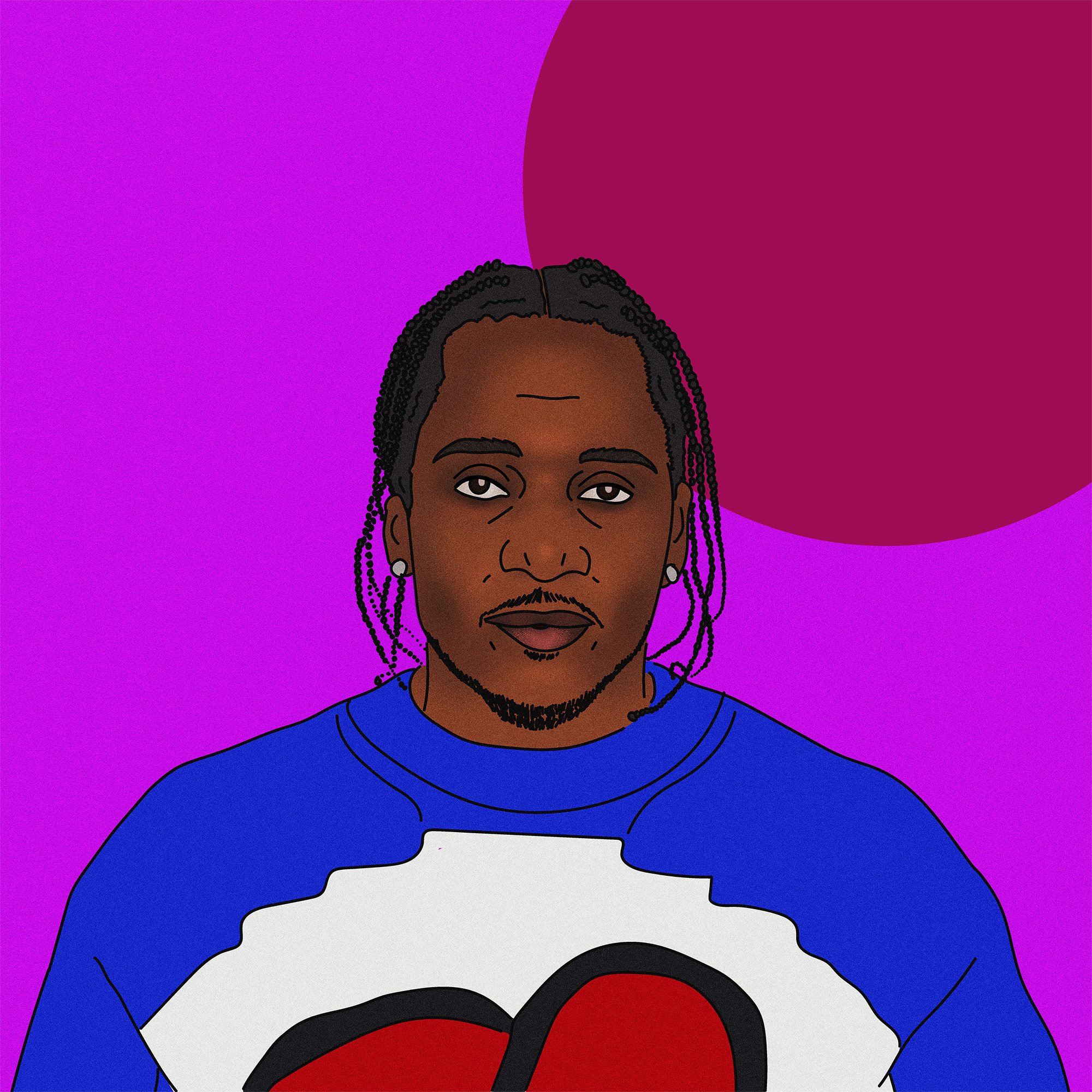

Fania Noel. Photo Credit: Ralph Thomassaint Joseph.

Meet Fania Noel.

Fania is a Haitian-born, Paris-raised afro-feminist, activist and organizer who is injecting a healthy dose of color in the discussions surrounding of race, feminism, climate change and identity in France.

Six years ago we met at a black expat meet-up in Paris, via a friend of a friend. In the years since, we have avidly followed her activism trajectory. Fania has departed Paris to live in Haiti, founded AssiégéEs, been a part of Mwasi Collectif, published “Afro-Communautaire: Appartenir a Nous Memes,” and has spent a considerable amount of time in North America.

And, do you know what’s really dope? Fania is one of the women that is an active part of the global Afrofeminist movement.

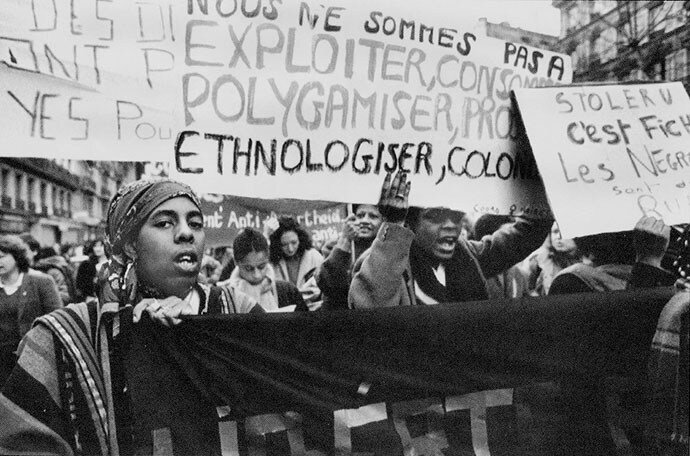

A movement that is on the rise, again, in France. In the years since the formation of Coordination des Femmes Noires and Mouvement Pour La Défense Des Droits De La Femme Noire, there has been a revival of Afrofeminism in France.

We reached out to Fania for a Q&A surrounding afrofeminism, solidarity, climate action and the black experience. Here’s what she had to say.

Tell us about Fania Noel.

I’m an afrofeminist, organizer, activist, thinker and sister, who is trying to be worthy of the inheritance of the Black Radical tradition on the continent and in the diaspora.

How would you define the Black Radical and what role the tradition plays in France?

When we talk about the mainstream and state, the Black radical tradition is totally shut out. [To define the black radical] start with the history of the Haitian revolution or independence groups in Guadeloupe and Martinique. The storytelling is that it’s a great mercy for France to “give” Black people rights and freedom.

Regarding the role the tradition plays in France...

On the activist side, we have a responsibility to center and contextualize the history of the black struggle in colonial and post-colonial France; and not always mobilize the Black American history. Even if we can build a bridge and understand how white supremacy and imperialism works, we have to be articulate about the differences.

s

There’s a growing feminist movement in France. In your experience is this inclusive to afrofeminists?

I hate the word inclusive. Feminist movements aren’t the garden of some [where] others are invited. My afrofeminism doesn’t care/want to be inclusive. It's enough itself. It’s a whole world and tradition linked to struggles on different continents, to the people from the largest diaspora in history. I want my afrofeminism to link and build political solidarity, movements and revolutions with organizations in Africa, the Carribean and the Black Diaspora in the global north. My eyes are on the black Atlantic, not really on the feminist movement in France. Afrofeminism is bigger than France.

During my first years in Paris, I noticed how I migrated into a society that separated me from the afro-french community. I immediately caught on to how it resembled black immigration in the United States. As an afro-french woman, what are your thoughts on this phenomenon?

As a black woman in France, I see the phenomenon is quite similar to when I am in NY, where I am an exotic Black, not a migrant Black, a “croissant ass n*gga”. The difference is sometimes I talk in Haitian creole so I get back to the usual place of Blackness --especially in Brooklyn. I think it’s important to be self aware of the whiteness projected on the “exotic” black. In explicit form, it shows in this context that you are not in competition with whiteness for a position or frenchness. (Your presence is not in context to a colonial past.) There is a blank page of multiculturalism without subtext. This is really with Black Americans because of this self-entitled idea in France that it’s “worse to be black in the United States” and that “at least in France we did not have segregation”.

Where have you found black/noir solidarity in France?

Black solidarity in France is mostly presented by [identity], like Haitian, Senegalese, and Congolese spaces of solidarity. These spaces mostly deal with issues of documentation, work, housing, and sending money to the country. They are really important. I’ve found deliberate spaces of solidarity based on common experiences through online groups like Twitter and blogs, which at some point become an [in real life] IRL group, project, or collective. Those groups created by my generation and the younger generations are not yet as strong and effective as the elders groups in terms of support --even if they’ve received more visibility due to the fact that they’ve mastered social media and the internet.

How receptive has the French public been to an Afro-feminist collective?

I am a kind of Bourdieusienne. I don't think there is such a thing as public opinion or a French public. If we’re talking about French politics, an antagonism exists with a type of afrofeminism like Mwasi. Our politics are anchored to a vision for the abolition of white supremacy, capitalism, neocolonialism and patriarchy. In terms of the media, it depends on the type of afrofeminism. In France, like everywhere, we see neoliberal Afrofeminism is more focused on representation, making the elite more diverse, and integration. This kind of afrofeminism is very media compatible like great Konbini style videos about hair, lack of shade of make-up, and (other forms of] commodification. As an activist, the core “public” is black people and to think about the antagonism and balance of power in terms of our politics rather than its reception. The goal is a mass movement where our people are involved, not just passively or as consumers. So it’s totally normal in a racist, capitalist, patriarchal society that a political [movement] proposing the abolition of the system is not welcomed.

“ It’s totally normal in a racist, capitalist, patriarchal society that a political [movement] proposing the abolition of the system is not welcomed. ”

In Sept 2019, you published a book, “Afro-Communautaire: Appartenir a Nous Memes,” can you tell Apres Josephine readers about the book?

The book is an afro revolutionary manifesto. I wanted to invite black people in France to think about a political utopia, not in terms of perfection, but to help design, construct and invest ourselves in a struggle and political organization. It came from the feeling that we’ve spent too much time having a position and not enough time having a political project.

Are there any plans to release your book in English?

I hope an English translation will be available in September.

What’s the importance of having a political project versus a position?

The position really fits in the neo-liberalism era, where image and PR are centered, so you just have to say a good word and it’s all good. The bar is in hell. With a political project it’s difficult to not be held accountable because you have to work in a collective, face failure, celebrate success, and most importantly: [invest] time. A collective project is based on a really different timeline, and process. [There’s an] african proverb, “If you want to go fast, go by yourself. If you want to go far, go in a group.”

You’ve been an advocate for women on many issues, including the impact of climate change on women. How much of a priority should climate action initiatives be for women of color?

I think climate change is already a priority for most of the women in the global south, as they are on the frontlines. When you have population displacement, women and children are under violence and precarious situations. For example, in Haiti, the anti-mining movement started after women reported a high rate of miscarriages due to the contamination of the water.

In the North, Indigenious women mobilizing in Canada and the U.S are an example of how grassroots movements are the key in the struggle for systemic change. In France, the mobilization in Martinique and Guadeloupe surrounding Chlordecone has been repressed by the government and carries other demands in terms of the colonial presence of France in those territories. The book by Malcom Ferdinand, “Une Ecologie Decoloniale” is relevant for french context about climate justice as linked with other systems of exploitations such as: capitalism, white supremacy, and patriarchy.

Who are some grassroots Afro-French organizers that you admire and/or that have shaped your politics?

I have to mention that those people, like me, don’t use the term Afro-french. The term is mostly used online amongst a small number of people, since most Black people in France relate to the country where their parents were born.We are mostly 1st or 2nd generation with strong links to those other countries. I don’t even use Afropean. I previously discussed this point in an interview with the platform Afropea.

Here are a few:

The collective Cases Rebelles, their work is just priceless, with a rare ethic.

Ramata Dieng founded Vies Volées after her brother Lamine was killed by the police. She started the fight for justice 12 years ago --going as far as the European court to try to get an indictment.

Sharone Omankoy, the founder of Mwasi Collective, is a social worker, doing politics at all levels; including the population under state violence (HIV migrants). She is really an inspiration.

The women who founded the Coordinations des Femmes Noires in 1976. Their 38 page manifesto and their struggles are important, our activsim is laid on their legacy.

Amzat Boukari-Yabara from La ligue Panafricaine-Umoja is a great thinker and friend. He helped me to build my politics in terms of political panfricanism. His book Africa United is a must-read.

Joao Gabriell is a Guadeloupean, friend, thinker, musician, member of Umoja and founder of Queer and Trans Revolutionary. He is one of the sharpest minds of my generation in terms of critical thinking on race, gender and capitalism. He’s now in Baltimore working on a PhD in history and the prison complex in Guadeloupe under colonial France.

Having spent a significant amount of time in the United States, is there a difference between blackness in Paris and blackness in, say, Brooklyn?

Blackness in Paris is definitely more African or Caribbean as a result of the direct proximity to the Continent and the Caribbean. At the same time, blackness in Brooklyn is more political, self-aware and organized. Also, I am haitian so Brooklyn is kind of a freeing place for Haitians. In Paris, I don’t have a lot of Haitians.

How should expats — who sometimes move abroad expecting “less racism”— connect to black communities in Paris? At times, some expats have argued there is no black community here, which I obviously disagree with, but I had to seek it out because of the language barrier and the community in France being seemingly based on cultural identity. What shapes the afro-community here?

Definitely, in France, the context is different. The strongest communities are cultural. In my opinion, it’s a strength. It makes black people in France more aware of neo-colonialism, internationalism and more engaged on this question. The existing Black communities are not the same as in the U.S. It’s more difficult for Black people in France to come together due to the universalism discourse, but more and more spaces, events, and professional spaces exist. If black expats can find white friends and spaces, they can find black people and spaces in Paris. France is the country in Europe with the most black people.

Do you have any suggestions where people should hang in Paris for discourse or just to be free?

It’s been three years since I’ve left France so I am definitely not the best person to ask, but Instagram is a good place to go.

For general events: @myafroweek

For art and culture : @afropea, @virginieehonian , and @noirpigment

For political events : @mwasicollectif and @liguepanafricaineumoja

For Black millennial events (talks/parties) : @letstalk_fr, @thewhylepoukwa, @book_and_brunch, and @readclub

For business : @afrolabfr