Amandine Gay is Changing the Narrative of French Cinema

Amandine Gay. Photo Credit: Otto Zinsou.

Meet Amandine Gay.

While Maxine Waters is teaching us to reclaim our time, Amandine is teaching us to reclaim our narrative. These two women from two different countries, two different generations and two different careers are both inspiring us to push forward and tell our stories.

Amandine is a filmmaker that embraces the politics of being. It’s why she is our first Les Gens of 2021 — she's just all around dope. A researcher, activist and Afrofeminist, Amandine is a woman who wears many hats. In 2014, Amandine imagined an inclusive cinematic future and began shooting the film Speak Up: Making My Own Way (Ouvrir La Voix), which documents the experiences of Black women in France and Belgium.

No more lip service. Black women were telling their own stories about life in France. With Speak Up, Amandine changed the trajectory of French cinema. You see, when the New Yorker's Richard Brody called the film a “vital film in itself and a virtual kit for the inspiration of other filmmakers; it’s an opening of voices and of paths," he was speaking the truth.

After watching the documentary, Aïssa Maïga, one of the most popular Black actresses in France, was inspired to spearhead My Profession Is Not Black (Noire n’est pas mon metier), a collection of essays by Black actressses that discusses racism in French cinema and theatre. Three years later, Maïga would continue to call out the lack of Black representation and racism in French film industry, but this time from the stage of the Cesar Awards. What a difference a film makes.

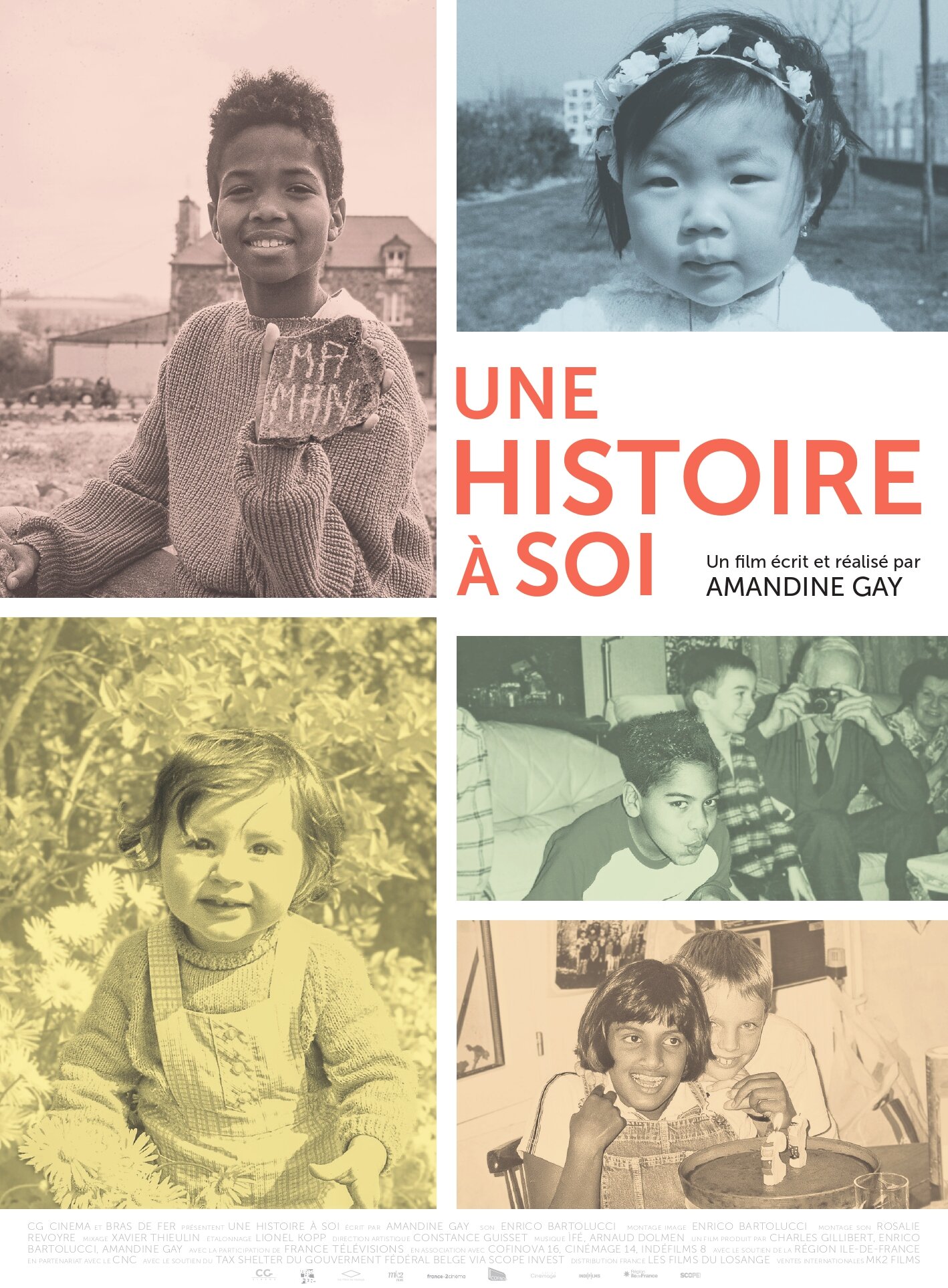

Now, four years after the release of her first film, Amandine is set to release the documentary Une Histoire à Soi on June 23rd. In her latest film, Amandine passes the mic to adoptees and centers transnational adoptees in the story of their lives. The film will be followed by her first book, Une Poupée En Chocolat, on September 23rd.

In December, we spoke to Amadine about life in the margins, decolonizing the mind and filmmaking. Here’s what the filmmaker who’s claiming our time by documenting some of the most fascinating narratives in France had to say.

I want to ask you about yourself and about life in the margins. Tell us about who you are and what life in the margins means.

I think it's important to start with the fact that I'm a transracial adoptee. I also identify as pansexual. So, I would say I'm a Black queer woman and a transracial adoptee. I was born in 1984, and I grew up in rural France in a white family that had already adopted a Black son, who’s a lot older than me. We have a different story because when he was a child, he was in foster care . So, they already cared for my brother, when they found out that they were infertile, and so they felt that it was a great idea to have another kid that was Black so that there would be two of us. I got to grow up with one other Black person, and even though we had a 12-year age difference you know, when I was a little kid, it was pretty cool because my brother was already singing Michael Jackson and listening to hip hop. We have a different story though. He knew his first family and he was actually raised in the French West Indies, so he had another experience of being a Black person – because his identity was first forged being Black amongst Black people. And, I would later find out that it's quite different.

What part of France are you from?

Lyon. Well actually, Montanay, a little village. When I was a kid there were cows. It was the real French countryside. It was really Catholic, right-wing, if not, far-right in terms of how people vote. My family was pretty cool. I think that because my great-grandfather on my mother's side, had learned to interact on a daily basis with an African person during World War I, so there were no particular racist remarks, [or] exoticism towards a Black person. We were like the other kids. I later came to find out that it was not the case for all transracial adoptees.

What about in school—were you treated fairly?

I was just talking about my family. The first primary school I went to, I don't remember much, but all my memories are pretty good. There was even a teacher that offered to buy a Black doll before I got to school so that the children would get used to the Black doll and that it would be less surprising to see a Black kid. So, the first school, I attended until I was 5. There was no problem, or I don't remember them. But then, I changed schools and the first day of school a kid didn't want to hold my hand. She was like, "I'm not holding your hand, you're Black," and I was like, "What?". I knew my brother and I were brown – our parents were different, but also because it was my family, I thought it was normal. I don't even remember the day my parents told me I was adopted. The idea was that my [birth] mother was a very courageous and generous person [but] that she couldn't raise me. And they were really fortunate that you know, she relinquished me. And that therefore they could have a child. That was pretty much the story I knew. And so, to me, it made sense. She couldn’t care for me, they couldn’t have children, it works for everybody. You know like, I got a family that loves me, I was really happy. And so that first day of school, I was like, oh, Ok, so apparently, I'm Black and it's so bad that she won't hold my hand. So what is happening? So that was the first moment when I realized there was a problem.

“I’m 36 and I would really like for us to be called adoptees and not adopted children.”

How was the issue addressed at school?

No, it wasn't addressed. I was saved from that scene because at that school, there was the son of my father's best friend. When that girl [said] that to me, he came up to me and said, "She's my friend, I'm holding her hand." And from then on, it was just a nightmare for many reasons. The first reason was that – you know, I think institutional racism. My parents were aware, and I would say mom, my mother, was the political one. I would say [she was] more aware of issues. There was no taboo to speak about race. But it’s quite different to have parents who are willing to learn a little, you know, like how to deal with your hair or your skin. But they did not understand institutional racism, so they had a really hard time defending me when it came to how I was treated in school, how my brother was treated by the police. He would be taken to the station because he didn't have his identity papers on him. The policeman in the countryside knew who he was, right? It took them some time. I think that by high school, they understood that what I was facing was racism. That it was not just that I was maybe too loud, or laughing [too much]. I would be denied congratulations. I would be president of my class, but I would still get punished. Since I had good grades, they could only punish me by not giving me the awards. In high school – by then, my mom would actually tell the teachers off, "If the only thing you have to tell me about my daughter is that she's happy, I'm good. Bye!” By then,[my parents] they got it. But it took them a few years to understand that. I would say, being in the margins is having a very different perspective on life, and your entourage, and your world than everybody around you, and having trouble explaining it, because they're not experiencing it.

So what did your parents think of Ouvrir la Voix ? What was their reaction to the film?

By the time the film was out, they had been schooled a lot. I think that [with] the experience of my brother they ended up understanding very well what the system was like with Black men. That was a great thing. And then there's been the fact that I've been working on those issues since, you know, my 20s. My end of studies thesis was on France's colonial history and how it was still affecting the present. By the time Speak Up was made between 2014-2017 – I was between 30 and 32. So they had been hearing about those things for the past 10 years already. My father passed, so he didn't see the film and he didn't get to see everything that happened. And that's pretty sad because, like, he's only known me as a struggling artist and the one that everybody wonders, “What she's goanna do?” And I wish he'd been there to see that it was actually amounting to something. My mom, she’s my cheerleader, we've been doing screenings in Lyon, in the little town next to where I grew up. She's on board. She’s fighting on Facebook.

In Speak Up you're behind the camera, but you've spent a portion of your career in front of the camera. Was there a reason why you stayed off-screen?

The first reason was that – you know, for a first film, there were a lot of things to be dealt with. The film is a dialogue between my perspective and the perspective of the women in the film, and you don’t really need to see me in the film because I’m everywhere.

One of the things that stood out to me was that names weren't on the screen. Was there a reason for, you know, not splashing names across the screen?

I often feel it doesn’t give you a lot of insight into who they are. Like knowing that Mary, 36, [is a] Nurse, doesn't tell me a lot about Mary. So to me, there were a lot of questions: How can we make this cinematic film? In talking-head documentaries, people are talking, and then you're gonna see a shot of their hands or shots of them walking in the street. There's always this sense of like, we're afraid of losing the audience so we got to give them something that changes on the screen. To me it was like we don't need to do that, we don't need some artifacts, because the point of the film is for people to sit in the room and listen to Black women for 2 hours. And so you don't necessarily know what they do in life, what you need to do is to listen to what they have to tell you. And there was a sense of like – you could create a collective, you know, not putting in their names, etc. It means you have to look for their humanity somewhere else, not in what they do but how they express themselves. The concept of the film is a conversation between Black women, and they could be Black women pretty much anywhere in the world.

What personal feelings surrounding race did hearing their responses bring forth to you, from you?

Well, I mean, what happened during the process of making the film [was] that I started being really emotionally tired. I created the questionnaire, then I tested it with some of my Black friends who grew up in Black families. The only thing that was really tough for me after a while, is that all the women would be downplaying the trauma and that's the thing I do, that's why it was bothering me. Out of necessity, I would say there was almost a year and a half between the moment we shot and the moment we edited the job, but it was actually quite necessary – like, I wouldn't have done it had I had the choice. But the fact that I didn't have this [choice] was a really good thing. Because after the interview, I really needed a break and I had a longer break. Maybe the one I needed. The thing that really struck me was collecting all those experiences. We organized parties at our house so that people got to meet. So, you know, especially to Speak Up, it was important, because I didn't want to have someone to collect this speech on-screen of women who have never met. I wanted them to have had these interactions in real life, too. It takes a lot of it out of you as a filmmaker. It's sort of like for two years and a half, I'm knee-deep in other people's life stories. Emotionally draining.

How do you create a safe space for those talking about race, particularly over an extended period of time?

Well, I think it's about –for instance, when you come from activist circles, you can see a lot of the power dynamics from the outside world. If you create a group just for Black women, that does not mean that you're not going to be appearing in some of the paradigms that come from the outside. And so personally, I believe that there is no safe space, because we can all come trying to be as empathetic and full of kindness as we want. But for me, I don't like to advertise that I'm offering safe space for anybody because I never know what's going to trigger them. I never know what's going to happen in a group. I can only be responsible for myself. So where I'm trying to work is on the power dynamics. Of course, I'm the filmmaker, I get to make the final decision but it's other people's lives. So, you know, how would I never want to be portrayed? I think that was really important to Speak Up because what motivated me to make the film was the fact that I was fed up with the way Black women were represented in French cinema. You know, it tends to be usually people from the middle class to upper, quite often white people, who study poor people, people of color. And to me, the problem is that it's never addressed. Opening my house is a way of bringing some more balance. I’m showing vulnerability, too.

One thing also that you've talked about is decolonizing the mind. I want to know what that means to you?

Well, to me, it's about decentering whiteness. I think that especially [in] my formative years, I would be talking to white people a lot. And when I was making Speak Up, I'm talking to the Black woman I was when I was 14. What did I wish I had heard before in my life? I wish I learned there were other Black queer people – that I was not on my own, something weird, or [that being queer was] something for just white women. If my film is directed at Black people, especially at Black women – especially younger, Black women, what's gonna give it a whole different feel, because I need to make them leave the theater empowered. I need to both warn them about what's to come and at the same time, not discourage them. So that's a really different tone and content for the work. [And] if I was going to tell some white people off like, it's not the same thing to me.

So in a previous interview, you mentioned how you proposed the character of a Black lesbian sommelier and were told that [they] didn't exist in France and were too Anglo-Saxon. And in one of your talks, you also talked about your interest in making a rom-com, but said you were centered currently on your work with activism, etc. in your art. So now I'm curious because there's activism in Black Joy – so can we expect a comedy from you in the next decade, half-decade, a rom-com?

The rom-com is coming. The next main project is the rom-com. We're also working on three other documentaries with Enrico, my partner. The first fiction that will be developed is the rom-com. I really love rom-coms. It turns out that you can be an activist and an angry Black lady and love rom-coms. For instance, the rom-com will be a Black couple – and it's going to be a straight couple, because France is not there yet. But our hero will have a Black lesbian sommelier housemate because I've been wanting to have this character exist for years, so she is gonna be there. The film is going to be political in other aspects. It's going to happen in high school. And so both love interests will be professors there. We're going to be talking about class because the one who's chosen to be there is actually from an upper-class Black family, and the one who would want to be somewhere else is from a working-class Black family. We’re currently working on the script.

When you were young, your parents put you in basketball and you also connected with people through social media for your projects. How are you finding connections and joy now for yourself?

I also forgot to say there is going to be basketball in the film because of “Love & Basketball”. I found a group called Ladies&Basketball, which was founded by my friend Syra Sylla, and it’s a very flexible way of playing. It was one way for me to get some joy before the pandemic because some of my friends were a part of the group too. It was nice to go play basketball [with] like another filmmaker and be like, "Oh my God! Editing is a nightmare." To be like, “Yeah, I know.” At the moment, I must say that most of my social life is via Zoom. A lot of my friends are a bit everywhere. And like I told you, I went to live in Montreal from 2015 to 2018 and we're actually waiting for our permanent residency but COVID messed that up too. We were supposed to wait for a year and now [we] wait and we don't know what's going to happen. We're going to get the papers at some point.

So you're going to leave France.

Amandine Oh yeah, leaving and not coming back. Hopefully...

The American media has begun to cover race [more] in France — finally recognizing racism. And, Macron has pushed back talking about America's obsession with race. How would you translate what's happening in France in recent years compared to, say, a decade or a half-decade ago when you were filming Speak Up?

Well, I would say that there's really been a turn in the public space when it comes to discussing race. Around 2012, I think the first blog labeled as Afrofeminist was “Ms Dreydful”, and a lot of blogs were created between 2012-2014 that were around Afro-feminist issues. So by 2014, I was writing for Slate and we started getting trolls a lot, especially from the left and far-left that were saying that we were racializing the issues, and that the only real issue was class. And what happened, I would say for the first time, compared to the previous generation, because of the internet – we didn't need the institutions to keep the fire going. So, even though people would get upset and say that we were, you know, importing racial issues from the States, they could not silence us because we could keep blogging if we wanted to. So it was just like, we don't need you anymore. That's where the power balance has shifted a little – even if there’s still no Black people being employed in a lot of French media. North Africans are a little better at getting employment in the newsroom, I believe, because of colorism. Some North Africans can be treated better than Black people or Asians. There are almost no Asians in newsrooms as well. All [of these] industries [are] really hard (in terms of economic and social capital) to break up, because at some point, per usual, you need people to want to hire you even if you have a lot of followers on social media. I would say the difference I’m seeing is it is harder to silence [what is happening]. For a very long time, the French narrative about France [was]: we are a country of human rights, etc. It was really efficient. I think because there was no social network, for instance, African Americans would have a huge part in perpetrating the “France, [a] liberating place” in terms of race for the generation of James Baldwin. There was this thing where every time we would try to talk about racism in France, even African Americans would be like, "Yeah, but you have it easier than in the US," even though, you know, the police killings are happening here too.

And to your Baldwin point, how can American expats be better allies when they're abroad?

I would say it's really happening. I remember, you know, in 2014 for instance, on Twitter, African Americans were just like, clueless, and they would be like, “We're not talking about you, we're talking about the US.” Like every time we were trying to be like, “Can you take it down a notch? [Saying] like, you are the most oppressed Black people in the world.” You know that the biggest Black community outside of Africa is Brazil. And the rate of Black people killed in Brazil [is] like three times higher as [it is] in the United States. And I was just like, well, you know, that's the US imperialism that you can see even in the Black community. So to me, it's really also, I would say, about being curious and being ready to address the fact that even as an African American, you might still be an American imperialist.

We are not Emily in Paris.

And I guess that's maybe the conversation that's the hardest to have. I think because Black French people are really taken apart from the nation's narrative. You know, like a lot of us even have trouble saying we're French, you know, like, I'm French on my papers, but there's no pride in being French in me. I compared America to India because those are two countries that are extremely nationalistic, you know, like – most Black Americans are Americans, right? A lot of Black people go into the army. I know it's a class thing also, you know, I know that like it's [a] way [to go to] university and stuff. But you know, even if a lot of Black people or people of color that go to the army [go because of] a lack of opportunities, I don't see the army being criticized – you know, like the army question being raised against imperialism, violence in the Middle East, etc. So I guess that's probably what’s kind of still missing to the conversation is really the link to nationalism.

What was the narrative you want to claim surrounding adoption, or being an adoptee in A Story Of One's Own?

Well, the first one is that we grew up – and that may be a strange point to make but in France an expression that is still used to describe adoptees is adopted children – I'm 36 and I would really like for us to be called adoptees and not adopted children. And [for] the state to consider us as adults, and therefore citizens, and therefore people empowered with a right to know about their past, and have access to their files. That shows you the power imbalance again. For me, the main thing was to make sure that I would give a voice to adult adoptees. You know when I told you about my life, my experience is one of an adoptee – You know, I have seen life through the eyes of a Black adoptee : even though as a kid, I had the experience of being a minority, I lacked racial socialization so as a teenager and an adult I had to reconnect with Black communities. I realized how isolated from blackness I was raised. And that's something I would never be able to catch up with. You know, I've been able to catch up with a lot of the music. I've been able to catch up with a lot of cinema. But some things – for instance, like, I don't know how to “tsk”, I don't know how you call that in English, but, you know, the sound you make with your tongue. That’s a very Black thing that I can’t do.

Yes, I know what you're talking about, which is I think is – primarily, like, Caribbean and/or African and Indian, apparently.

Yes. I didn't know.

My friend came from India. She came to Chateau Rouge, to my area, and she was like, “Oh, your neighborhod feels/sounds like India.” I was like, interesting. She felt at home.

Yeah. There are quite a few things [where] I know I don't belong – even in terms of, for instance, people discuss Black love a lot. And I was like, well, you know, it's taken for granted that Black love means that you are going to be able to feel more comfortable with a Black person. But for adoptees, when you've been raised by white people, you know, your cultural references, and the people you've been used to being cared with, or being used to care for, are white people. Having adoptees talk about their lives as adults [is] also providing this opportunity to show that it's not so easy for us to go back to our roots in everything that it means, [like] going back to our birth countries. I often tell a story – I had a friend, it's her first time to Rwanda. It was really traumatic for her because she didn't have the cultural competency, right? And so, you know, in Rwanda, for instance, if your hair is shaven as a woman it means that you're a minor. It is seen as extremely vulgar to eat on the streets, especially for a woman. And so she got there and she had her hair shaved. She was in her 20s, but she seemed pretty young. And she went out with a white partner who had a beard. So even though they [were] the same age, people thought he was much older than her. And because she looked [like she was] from Rwanda, people assumed that she speaks Kinyarwanda, which she [does not].

So when she got there people would, like, yell at her saying, like, “You should go to school,” you know, because they thought she was like, a bad girl, who instead of going to school, was with an older, white man. And then they would shout at her in the street and she would not understand. And they would be like,"Yeah! Stop pretending you don't speak the language. Like you think you're better than us," etc. And then one day she ate an ice cream outside and people just lost it, you know. And so she had this sort of mythical image, right? Of like, going back to her roots, that it was going to be magnificent, she was going to find her people and once she gets there, you know, your people only come at you. And so you live this life as an outsider within, you know, white community. And when you get to Black communities, well, you're not like us either, you know, and so you need to be able to navigate those identities, to navigate the fact that you will never be truly one or the other and just have to make peace with that.

That's the point that's made in the film and so to me, that's why I'm trying to show our experience first, so that it’s going to benefit younger adoptees, but also [to] show how political and never-ending this issue is. You know, it's not like bringing us in your family and that's it. We were [a child alone] and now we have a family. Problem solved. No. Being an adoptee is a lifelong issue, like when you are going to try to have children yourself, or when you become grandparents or when you have, you know, health issues – like, I can give a personal example. I had fibroids and I wanted to have a hysterectomy. And again, because we are extremely patriarchal societies, doctors don't want to give you a hysterectomy before you’ve conceived because you’resupposed to make babies. And so the argument that was given to me was that if there were priors of uterine cancer in my family, then I could get into surgery, but I was born under X, (the French version of closed record adoptions). So I have no idea what my medical history is. So I can't get the procedure I need because I don't have access to my birth information, my birth family health, or family information. So this impacted my life in my 30s, you know, and so these are examples that show how adoption is always a part of our lives and how it reflects, again, patriarchy, accompanied by racism, geopolitical issues, etc, etc.

Who are some Afro-French filmmakers that you like, or that have played a role in shaping how you create?

Well, definitely Euzhan Palcy because she's the first one that I have heard of and that I was like, oh she won a Ceasar, which was amazing. And, also for a film that’s centering Black folks. If you look at La Rue Cases-Negres, it's really a story about [the] politics of Black people in the Caribbean and I thought that was rather amazing. And Alice Diop, I really loved La Mort de Danton which was her second documentary. She's following a Black man who wants to become an actor in France and you're seeing him getting all the institutional racism from acting school and from the industry. It’s a beautiful film. And I was really astounded when I saw it. Another one, she’s not French but she studied in France, which makes her like one of the first Black French women that I could think of to make a short film in 1972 and she's called Safi Faye. And she came to be a very important Senegalese filmmaker. And in the same generation, there is Sarah Maldoror, who was a Pan-African activist and creator. She really has a sort of revolutionary life. She would go and study film in Moscow. So like, you know, she's like a real hardcore communist, and then she went to film the liberation war in Angola. She married a freedom fighter and went on to become a very prominent political figure there. And so those are very important. Maldoror actually passed this year because of COVID. The biggest homage she got was from the U.S.

I know that Melvin Van Peebles had a huge impact on your work, so I am curious, what film impacted you the most? It doesn't actually have to be a Melvin Van Peebles film either. Just, I guess, what would be considered your favorite film?

Well, Sweet Sweetback Badass Song : A Guerilla Filmmaking Manifesto is the book that made me realize that I too, could make a movie outside the industry. Without Melvin, I would have never had the courage to make Speak Up, so yeah, he’ pretty special to me. Otherwise, one film that I've seen many, many times that I always like seeing is Secrets & Lies by Mike Leigh, because it's the first time I saw a depiction of adoption, that centered a Black woman’s experience. I guess that's why it touched me so much – I felt it was realistic and not exploitative and stressful and it's really, really well done. And I tend to watch it at least once a year and every time I cry. So this is one that really had an impact on me. The other one --not necessarily my favorite film-- and it's not at all, but it's really had an impact because I didn't get it the first time I saw it and then I got it. It’s Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing. I remember when I was a young Black, french woman and really sort of, you know, believed in the republican universalism model and thinking that we have to be a homogeneous, you know, society and we all have to melt in the republican crucible. The first time I saw Do the Right Thing, I was like, that is such a negative perspective on life. I think I was like 16, 17. I didn't get it. And then I went to Australia, to my year abroad to study when I was 21, 22, and one of my roommates was from Malaysia, and we were really good friends because he was my first friend of color who liked punk music and a lot of things that I had trouble connecting with my black friends or friends of color. And when we were talking about race in France, he's like, oh, so you must really love Spike Lee and I'm like, oh no I saw one film and I hated it. And he was like, I think you should watch it again. I was like, ok OK. So I watched it again when I was 21 and I had had a Black political education by then and I was like, Oh, I get it now. So yeah, Spike Lee’s work means a lot to me for that.

And I think, what's really interesting about movies, is how, if they're really good like they're going to just generate a strong reaction no matter what. And the time the people are pissed at what they've just seen or saw --maybe they didn’t get it or maybe it's just gotten them at some point that they didn't want to look at, and I think it's been a good lesson. For instance, there was one screening of Speak Up, when the Q&A just started, a young Black woman took the mic and she was really angry. I don't really remember what she said, but she was really critical of the film and really angry. And then we did the whole Q&A and it lasted for an hour and at the end of the show, she came down to see me as I was going out of the theater. And she said, look, I don't know what came over me. I actually really enjoyed the film. I don't know, it must have pushed some buttons and I didn’t want to be aggressive like that in public, I was like, no, you're okay. And I think I learned that with Spike Lee. I was like, okay, you can have whatever strong reaction. As long as the film moved you, I’m happy.

There's always a moment. During Speak Up, I started texting friends, asking them a random question surrounding desirability. Because, I think many of the women preferred white men when they were growing up. But as a Black American, I had never had that experience [as an “Xennial"]. So I was kind of like, wait, was this something any of you experience? It really sparked a conversation.

My last question is – what Afro-feminist organizations would you suggest young people start looking into, where you know, I'm sure there might be people starting out and they're trying to look for organizations to get involved with. What would you suggest be the first place that they start, or how should they find their way in terms of activism?

Amandine Mwasi Collective and Parlons des Femmes Noires/Afro-Fem based in Paris. Sawtche Collective in Lyon ; Collectif OBA in Marseille and La CAAN (Coordination for Autonomous Black Action); It's not strictly Afro-feminist but I know that it's been created by people who are also members of Afro-feminist collectives. I. So that's another thing you can get involved in. I know that now more and more schools have Black groups. So for instance, at Sciences Po there is Association Sciences Po pour l’Afrique and Sciences Curls. So this is really new, like – back when I was in school, I was the only Black person in my promotion. There were four promotions and so there [were], like, five Black people in all. Nowadays in universities, you find more and more Black students starting Afro-Caribbean networks or, you know, collectives addressing anti-blackness (Sciences Curls is using the theme of hair in employment to mobilize for instance). Also you have Blogs, and Twitter and Instagram. I mean, I'm already kinda old, like, I know that it's no longer happening on Twitter, it's Instagram, Tik Tok and places I probably don’t know now for the real young ones.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.